How Do You Determine What is Right

/It might explain why we disagree so much.

Overview

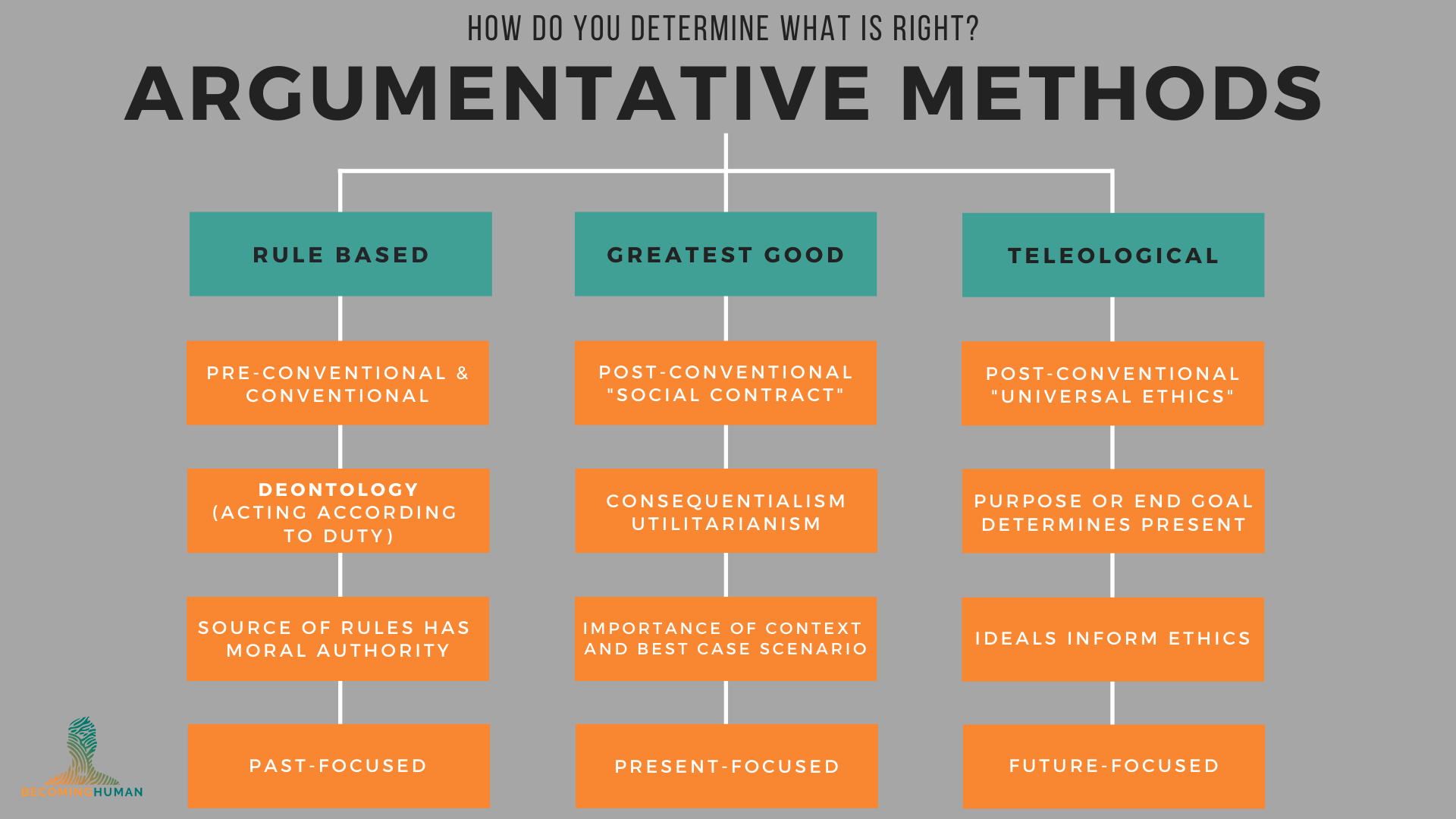

There are three general methods humans typically use to develop their ideological conception of ethics.

These are based on Lawerence Kohlberg’s “Methods of Moral Reasoning” and the concepts of Deontology, Consequentialism, Utilitarianism, and Teleology.

Using different methods will lead to vastly different outcomes — which is often why some people have irreconcilable disagreements.

We need to know (1) what methods we use to understand the world and (2) the methods being used by opposing parties.

Introduction

The distance between our culture’s propensity to vehemently argue and our culture’s ability to understand what is causing said argument is verging on the infinite.

From conflict mediation to the classical modes of reasoning we tend not to think very deeply about the essence of our perspective and how to effectively communicate it.

Yet, as a more foundational issue, we seem even less inclined to understand the cause of different arguments and how it shapes the way we disagree.

Contents:

Why Do We Disagree

Rule-Based Method

Greatest Good Method

Teleological Method

Part One — Why Do We Disagree?

Consider any number of hot button issues:

Gun control.

Human sexuality.

Nation-state law enforcement.

War.

Economic policies.

How to raise children.

Whether or not you should introduce said children to St. Nicholas.

Seriously, the list is endless.

We are very good at talking about divergent perspectives — we are less proficient at understanding how we arrived at our conclusions.

How do you know what is right or what is good?

Elsewhere, I’ve covered various categories and approaches that help us formulate our arguments, but what determines the direction by which we conclude a subject?

More specifically, how is it that two people can have the same information or data or empirical experiences and still arrive at completely different conclusions?

How is it that someone can be completely convinced Donald Trump is the worst president ever and someone else thinks that he is, quite literally, ruling by divine right?

How can one person be absolutely convinced that gun violence should lead to the banning of guns while someone else is equally convinced that guns aren’t the problem?

The list goes on ad infinitum.

For some of these situations, it can be that people are working with different information, data, or empirical experiences. It could also be that they are using different approaches to making their point. A logic-based argument looking strictly at data is going to arrive at different conclusions than a value-based argument or one founded on pathos. There is also a difference in where folk’s moral authority comes from.

But there is a larger meta-conversation here that can impact such divergent outcomes even more substantially.

Different outcomes are often arrived at because people are using different methods to determine what they think is right.

Essentially, the method you use to establish an argument is a lens that impacts how you will then interpret information. Your methodology is less about your approach to a specific argument or the content involved in the argument — it is about the general perspective that filters any information in a particular way.

Your method of moral reasoning is like an operating system.

And there are three general categories (or methods) that folks might use which also parallel the most common methods of social ethics: Deontology, Consequentialism, Utilitarianism, and Teleology.

Lawerence Kohlberg is the primary reference here and the following is based on his “Methods of Moral Reasoning.” Kohlberg was a psychologist expanding on Jean Piaget’s “Moral Development Theory” which was based on the cognitive development of children and how humans decide what is right and wrong.

Part Two — Rule-Based Method

Kohlberg articulated his moral development into three categories with two stages each:

Pre-Conventional

Conventional

Post-Conventional

Pre-Conventional & Conventional: Four Reasons We Follow Rules

The Rule-Based method actually covers the entire first two categories and the accompanying four stages.

Pre-conventional moral reasoning basically asserts that we determine what is right based on following rules. There is a rule or a law and that determines what we ought to do. The most primitive obedience is that we follow rules to avoid punishment. On a slighter higher moral ground, we may follow rules to gain a reward.

Our motivation for this approach may be positive or negative.

If you are familiar with psychology, this is Classical Conditioning (think: Pavlov’s dog).

Further, the approach could be framed by what Kohlberg called “Conventional” reasoning — where we follow rules not just out of pure obedience, but because of social convention. We want to appear correct and acceptable within society. This would be his third stage.

The fourth stage is similar:

We may follow a rule because doing so will bring order to society. Kohlberg literally called this “Law and Order;” where we follow rules because we believe it is the best societal instinct for our species’ survival.

How do we determine the right thing to do?

Look at the rules or laws or principles within our given setting and follow them.

While we might still need to argue about how a specific rule is applied, the concern is that we know what the standards are and we simply need to enact them.

Deontology

Within the field of ethics, this is called Deontology which is best understood as “acting according to duty.”

Whether it is to avoid punishment, gain a reward, adhere to social convention, or because we think the rules are best for society, we based our ethical stances on rules and norms.

You can probably sense a potential problem here:

Whose rules?

One of the key ingredients to any deontological system is that a source of moral authority must be named. In order to have a rule or law that is corporately accepted as a governing force, there must be an objective, predetermined origin that sets the standards for us to utilize.

In America, this is the Constitution — meaning we are a rule-based society (just like a lot of nation-states because, well, that’s the easiest way to control and stabilize large groups of people; you need general rules).

For religious traditions, this is usually the role of their sacred texts.

Yet, another source of moral authority can be a tradition — the rules, principles, or standards that have been agreed upon over time.

The key is that there is a source outside of the human person that tells us what to do. Moral authority is not sourced on human reason or human experience (rationalism or empiricism — which are the other common sources of moral authority). Our ethical constructs are outsourced — whether to a deity, a monarch, or some larger conglomeration of human existence.

There are lots of weak spots to this field and countless scholars have continually developed adaptations to account for them, but, generally, deontology is the most criticized ethical methodology.

However, the ideal notion of this method is that making decisions is easy because you only have to refer to established principles.

Spoiler alert: The Rule-Based approach is never quite that easy.

Part Three — Greatest Good Method

Maybe you see some issues with the Rule-Based approach and you think:

What if we just decided on what to do and how things ought to work by looking at the various factors of a situation and doing what makes the most sense based on those factors.

Framing your perspective this way is called the Greatest Good Method.

An important component of this method is marked by an acknowledgment of compromise. There is a chance that the final decision won’t be ideal (because of the pertinent factors). There’s also a chance that you may have to break the rules (again, based on the pertinent factors of a particular context).

Simply put, this method seeks to bring the most realistic good possible in a certain moment.

Some keywords:

Realistic good possible.

Context and situation.

One issue with this method is that it is much more relative than the Rule-Based method (which, as it happens, also is an apparent strength). Situations are subjectively based on a conglomeration of factors.

If Rule-Based deontology is about making decisions based on the past (with benefits such as not having to discern the right thing in the heat of a moment), the Greatest Good method is about making decisions based on the present.

Moral authority, therefore, is not sourced in tradition or some origin of rules, but on experience and reason.

This issue of relativism forces adherents to consider other means of consideration. If everything is relative, then you can’t argue for or against someone doing something terrible (except that you happen to not prefer it). Relativism can be used however the user sees fit.

So how do you determine what is good and right? Two ethical perspectives can be used in conjunction with the Greatest Good method.

Utilitarianism

One way that people have used to make decisions for the greatest good based on a specific situation or context is to determine the correct outcome based on what is the greatest good for everyone; or, at least, the most people possible.

Some argue that the Epicureans were the first utilitarians (they argued that decisions should be made based on what evades the most pain and brings the most pleasure, or good).

But Jeremy Benthem and John Stuart Mill are the primary references for modern utilitarianism and they claimed you could actually measure the results of happiness and societal benefit of particular actions and, therefore, configure what the best decision would be in the present for the most people possible.

Decisions can be made to maximize utility to the largest number of people.

This means the rules aren’t important because — despite what deontologists say — the rules are built on truth, but moral custom; which is often outdated.

Societal goals of happiness, goodness, and health can’t become outdated.

Every decision, then, runs through the filter of greatest utility — the best-case scenario for as many people as possible in the present moment.

Utilitarianism does have some future-tense to it (the goal seems to be based on ideals, most of the time) and there are problems with the “tyranny of the majority,” but as opposed to inquiring as to rules or principles you are just making practical, measurable decisions in the present for the best-case scenario for humanity.

Consequentialism

Utilitarianism isn’t the only ethical perspective that interacts with the Greatest Good method — because what if the greatest good is a bit more confined: Your tribe, your nation, your family, or, maybe, just you?

Consequentialism is an approach that is also highly formed by the present (while also having to work to define more objective forms of goodness so as to avoid people getting to do whatever they prefer).

As opposed to utilitarinism, however, is that the decisions are based purely on the consequences of an action.

If the consequences will be good, then it is the right decision.

If the consequences are bad, it is not the right decision.

More emphatically, consequentialism is highly based on the importance of context and particulars. Sometimes this is framed as moral particularism (that what is good or bad can change depending on the context), but consequentialism is almost a reaction to deontology:

There are no general principles that can be applied to every situation.

So, you have to, in each moment, figure out what the best thing is to do.

This could be based on the greatest utility or everyone or it could just be what you sense is best given the situation — but the point is that you determine the good in connection with the context, not rules.

Kohlberg had his own psychological take on this — The Social Contract.

This is slightly a riposte to political philosophy because Kohlberg is arguing that the people must uphold a social contract by garnering the most reasonable good even if it means ignoring or challenging rules and laws.

Part Four — The Teleological Method

If Ruled-Based and deontology is based on the past and following right principles and the Greatest Good is based on the present and focuses on the particular contexts for creating good outcomes, then the Teleological method is both very different and, yet, can also work in conjunction with both of these methods.

Teleology is just from a Greek word that means “ends” or “purpose.”

Aristotle had a whole thing within his “Four Causes” that has been quite dismissed biologically, but the emphasis in ethics is that we can know what to do based on ultimate ends or goals.

There is an aim or purpose for how everything is supposed to be.

We seek to live in the present based on those goals and their implicit ideals.

To which you may notice — teleology often can interact with subjects like consequentialism and utilitarianism or even deontology. In this respect, teleology becomes a means to inform the rules or the criteria for good consequences or what the ultimate “utility” even is.

This works because Teleological ethics is concerned with both what is right and what is good (a natural mix of Rule-Based and Greatest Good methods).

Teleology derives moral obligations from the ideals that are meant to be achieved.

The Teleological method is for the idealist — starting with big picture goals and working back to the present.

For Kohlberg, this correlates to his final stage which was also “Post-Conventional” which he called “Universal Ethics” — which is similar to Utilitarianism but takes it even further.

The surface can only be scratched here — there are many different types of teleology (as well as the other ethics mentioned) and there is much more that can be said about the advantages and even the blemishes of teleology (it isn’t perfect, by any means).

Part Five — What Happens When We Use Different Methods

All of that unnecessary verbosity is just to, hopefully, give us language for seeing that our disagreements might not be based on the same methods.

It can be a good, healthy practice to zoom out and see that there are actual descriptions for how we arrive at our perspectives and for how we filter and interpret the world.

When you come across someone whose argumentation seems a little funky, it might not be because something is wrong with them. It might be that we are each using different lenses to interact with the world.

You can see how this works — if someone is making a claim about the death penalty from a teleological perspective and someone else is approaching it from the greatest good method, they can have all the same information and data and still reach different conclusions.

Because the one person is interpreting the data through a perspective that has different processes than the other person.

Now, if both parties are using the same method and are on the same page about their approach — then argue away. Work with the information and come to some conclusions.

But if the approach to the information and the methodology are incongruent, the least you can do is acknowledge that both parties aren’t on the same page.

At best, you can utilize the varied perspective to make help both parties see the issue differently and with more nuance.

The point, I suppose, is that if two people have different starting points that inform what they think is going to be the most helpful way to interact with given information in a certain situation, then it doesn’t make sense to try to argue using those different methods.

It’s like playing a game against someone — except you are each playing a different game.

The next time you find yourself frustrated that someone just doesn’t get it, maybe consider that they do get it, they are just using different means that naturally take them to different conclusions.

Even though your lenses are different, according to your established methods, you might actually both be right.

So as you enter disagreements:

Know which method you are using.

Know which method the other person is using.

Because, really, your disagreement might not be about the content in question — it might simply be about the method.

And if you want to argue about methodology — have at it. At least you will be arguing about the real issue.

But if we go on playing a game against someone who is actually playing a completely different game, confusion will win in the end.

![Three Reasons We're Lonely - [And Three Responses For Being Less So]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5963d280893fc02db1b9a659/1651234022075-7WEKZ2LGDVCR7IM74KE2/Loneliness+3+update+%283%29.png)