Putting St. Nicholas Back in Christmas

/The story about where Santa Claus came from versus the story of the real St. Nicholas.

I have some problems with the whole Santa Claus thing.

Here’s the first problem — from the foremost opportunity, I have told my children that Santa Claus is not real.

Yes, they know we are the ones putting forth presents and they know the dude in the mall is wearing a costume.

But the reason my family abstains from this tradition is not that I don’t want to lie to my kids (which I don’t). Nor is it because the Santa Claus narrative is worthless or bad (which it, kind of, is).

My reasoning is different.

And as it is the feast day for the saint called Nicholas (December 6th), I feel compelled to share my reasoning.

Because it's a shame St. Nicholas has been reduced to a single day with slight reference to who he actually was.

And it’s worse that Santa Claus has usurped his fame.

Part one — How We Got to Santa Claus

The meandering journey of St. Nicholas’ evolution to Santa Claus is a relatively short one. Santa Claus, as we know him in modern America, hasn’t been around that long. Many historians have tracked the evolution quite well (like this article from National Geographic), but I believe there is something else going on here, hidden in the details.

Early America didn’t have much to say about Santa Claus or even Christmas. As the primary population comprised the leftovers from England and other European nations, religious vitality was a bit on the low end. The Puritans changed that. Their approach to Christmas, however, was quite fierce. As the holiday had become relatively commercialized and had adapted an immense amount of pagan interference, the Puritans banned Christmas in 1644.

Any notion of Father Christmas departed with it.

Later, as the Dutch began their own imperial convergence in the world, they brought with them the tradition of Sinter Klaas. Though the Reformation did away with most veneration of saints, Saint Nicholas’ popularity continued. The Holland faithful particularly esteemed this saint and, in 1773 as their population grew in the new world, they brought the tradition of honoring Saint Nicholas on the anniversary of his death.

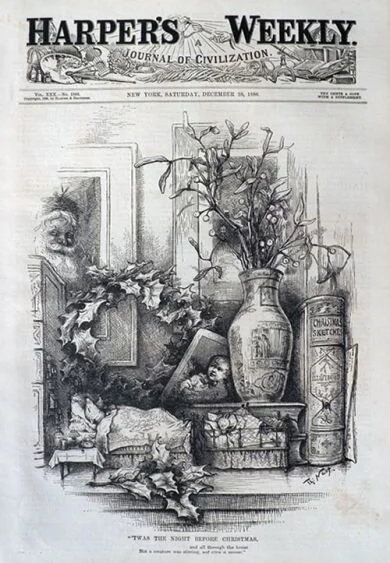

Thomas Nast took the image of st. nicholas to a new level. Upgrading “An account of a visit by saint nicholas” and its mini version and giving him the image that survives today.

The imagery of an elder man in bishop’s robes began to circulate and Sinter Klaas slowly took on the Anglicized linguistic form of “Santa Claus.” By the 1820’s, this Dutch tradition had become adapted into much of the American culture. This coincided with the poem, “An Account of a Visit By Saint Nicholas”.

Which eventually was called “Twas’ the Night Before Christmas.”

Thus, Santa Claus began to take on the imagery for which he is seen today — a jolly, plump elf like figure with reindeer and toys delivered through a chimney for deserving children.

That’s all it took for Santa Claus to begin his arrival. A few decades and the right public image.

Like I said, a meandering journey that is, in the span of history, quite new.

Did people feel so moved to pay their homage to the once dear saint? Probably not. But this Sinter Klaas guy was pretty cool. Maybe it was cultural appropriation. Maybe it filled a winter festival void. Maybe, as appears to be true, the getting black-out drunk and using Christmas to administer all sorts of illegal activity needed to be domesticated.

Either way, Saint Nicholas was getting a makeover.

Part two — Santa Appeal Sells: The Modern Growth of Santa Claus

However, while well-meaning religious folk and quaint poems helped catalyze the remembrance of Saint Nicholas, popularity was enhanced by a greater force.

Profit for commercial stores.

Industrialization made way for immense access to products that altered the lifestyle of the age. The local general store became the supermarket. And the supermarket became the outlet for the sale of such products that were once a luxury.

By the 1820s, the Christmas season and the rise of an epochal gift giver was an opportunity to boost sales. If you’ve got a cultural icon who seems to be putting toys and goodies in stockings, what better way to grow your margin! By the 1840s, stores were advertising holiday sales and enticing families with life-sized Santa Claus models. The real winners took this a step further, having a live Santa at their stores.

Sales went up.

By the 1920s, having a Santa Claus in attendance to inspire gift buying was no longer innovative, it was the standard. Do you know what else started in this decade? Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade, in 1924, complete with a live Santa capping off the parade.

It didn’t stop there. In 1926, Macy’s teamed up with a reindeer meat salesman to have a full display of Santa, a sleigh, and reindeer. Montgomery Ward got in on the action in 1939, creating a coloring book for kids who came to the store. To set themselves apart from Macy’s, they added a new figure — Rudolph (though he was almost called Rollo).

You bet parents brought their kids and, in turn, bought lots of stuff.

And sales, indeed, boosted.

Around WWII, the songs followed. 1934 saw the first rendition of “Santa Claus is Coming to Town,” which led to the idea of Santa having a list that he checks twice. But the demand for Christmas music in the 1940’s saw previous tunes about Santa hit the charts with new songs like “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer”, “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree”, and “White Christmas” being created to capitalize on the cultural phenomenon.

Interestingly, many of these songs were written by Irving Berlin, a Russian Jew.

Christmas and Santa Claus as we know them today were finally born.

Not out of sentimental fireside chats about a real narrative, but out of an attempt to make money. A shopping campaign needs to capitalize on consumers so they play with the story. The song needs a better chorus so they add some details.

Soon, those commercial ploys bolster the narrative.

And, conveniently, everyone played along.

I wonder if the Episcopal minister who wrote that quaint poem, Clement Clarke Moore, or those early Dutch attempting to honor a notable saint would be pleased with where America took these traditions.

What I don’t wonder is how Saint Nicholas would feel.

He would be pissed.

Part Three — The Benevolent Gift Givers: Santa Claus Has Some Competition

In 2011, I had the opportunity to witness an event that, as one enmeshed in the modern version of Santa Claus, forced me to reconsider this Christmas tradition.

A large room was filled with life-sized models of the “Spirits of Giving From Around the World”. I walked around, reading each inscription of the over twenty different versions of an icon I assumed was an immortal singularity. That’s when the idea of Santa Claus as the North Pole toy-making wonder was put in his proper place for me. I recognized its newness, its commercial driven emergence, and its stark contrast to the saint that was its foundation.

Of course, there was Sinter Klaas and Kris Kringle of the early American rendition inspired by the Pennsylvania Dutch. But there was also Grandfather Frost of Russia, the good hearted man that traveled around Russia on New Year’s.

Or Hopsodar of Ukraine who, on January 5th (Eastern Orthodox’s Christmas Eve) inspires households to decorate their home with a special shaft of wheat tied with a ritual towel.

Or the Haitian Woman of the Carribean, opulently dressed and carrying a baby along with a basket of delicate fruit.

There’s Le Befana of Italy who comes down chimneys with gifts and firewood.

Dun Che Lao Ren of China (Christmas Old Man) who arrives during the holy birth festival.

Julesvenn of Norway who hides lucky barley stalks around the house.

Viejo Pascero in Latin America who brings holiday treats and poinsettias or even chickens for families.

Some of these folk icons have long disappeared (often replaced by our much more profitable Santa Claus), but every life-sized model I saw had one thing in common:

They honored the tradition of a gift-giver who brought help to those who needed it.

The angelic beam of Santa Claus faded. I thought, “There’s more to this tradition than I could have imagined,” and I began asking questions about what else I had missed in the Santa Claus narrative.

Part Four — A Different Night Before Christmas

Imagine being a lowborn family in the 4th century Myra of Turkey. It is the night before Christmas and, all through the house, no one had eaten, not even a mouse.

Food was hard to come by for your household and, with no fire to keep you warm, your family huddled together waiting for dawn to break — in hopes that the man from Myra might show up.

When all of the sudden,

a clatter was heard

and you sprang to the door

to see what occurred.

But as you opened the door,

he was gone in a flash.

So you ran to the window

and threw open the sash.

A loaf of bread sat there,

such a gift in your need,

on this cold Christmas night,

with the children to feed.

Then you caught a glimpse

of the one they called saint.

For it was Nicholas of Myra

and his mission

was anything

but quaint.

You see, this man named Nicholas who resided in Myra was a bishop of the early church. He was known for being a radical confrontation to the church who had lost its way in the 4th century and was willing to stand against any empire that dared squelch the revolution of Jesus. He was known as the Benevolent Gift Giver — but it wouldn’t happen as a fat man in a red suit magically sweeping down the chimney to give affluent kids toys they didn’t need.

It would be a knock at the door after sneaking under the cover of darkness to avoid the authorities. Then ramming the door open to rescue women from slavery.

Or leaving a bag of gold for the family that was about to lose everything to the government.

Adam English captures the identity of Saint Nicholas with this image:

You’re on your last crust of bread? Keep an eye on that window, because St. Nicholas might show up.

This gift-giver was about lifting the lowly, the misfits, and the abandoned to health and life and peace. He was known as the patron saint of anyone in dire distress.

One that confronted the empire, broke the rules, and changed the world.

Caroline Wilkinson, a facial anthropologist at the University of Manchester even believes that Nicholas’ nose was permanently broken, possibly from the persecution he endured via his gift-giving (check out this documentary for more). This is the guy who gave his entire inheritance to over-taxed peasants and was known for standing between an executioner and the one condemned to death.

He was less of the guy who would show up with reindeer to give your family a magical Christmas morning and more of the guy who would kick down the door of the rich, take their money, and give it away.

St. Nicholas would probably be killed in our culture today.

This isn’t what we want from Santa Claus — but I think he would be equally disturbed with what we’ve done with him and this holiday.

Because his gifts, his way of life, was a response to the incarnation ideal he so vastly patterned his life after. His gifts were meant to bring peace to a world that desperately needed it. His gifts were an attempt to take this Christmas story and practically manifest its very physical effects in the world.

There’s a story about three girls who were about to be sold into slavery because of their impoverished debt.

But they woke up the next morning to find a bag of gold — enough to pay a dowry to get married and, therefore avoid slavery.

Sounds like a Merry Christmas to me.

That’s who the real Saint Nicholas was.

Conclusion — Would the Real St. Nicholas Please Stand Up?

How did we take such a beautiful story of such a revolutionary man and turn it into this?

Some immortal figure in an uninhabitable location with a bunch of elves (are they blood elves? Are they descendants of Lothlorein? Are they slaves?) making the same gifts you can get at the store?

Seriously, this comedic sketch captures the situation quite well.

Then we have to find ways to prove that this dude can use actual animals that actually exist to fly around the world to every home in a given night.

Except some houses get lots of toys and some don’t — and it happens to coincide with their parent’s wealth.

The myths of a culture tend to reflect the desires of a culture.

That’s how we did this.

Because a quaint Christmas morning, with a bunch of new items to be opened by surprised children while we sip a hot drink speaks to the comfortable affluence we desire.

It’s just that Saint Nicholas seemed to be driven by the opposite.

Then there’s the further irony that this narrative has been driven by the commercial profits of large corporations. Apparently, everybody wins with our version of Santa Claus.

Alas, I tell my children that this version of Santa Claus isn’t real.

I tell them it is a story.

It is one way that people remember the saint called Nicholas, even if it is a bit deformed.

Yes, to qualm your fears, we talk about not ruining the surprise for families that still do this. If that is your way of participating in the story, that’s fine. And we still do some of the things associated with Santa, just without the clandestine nature. We are all aware of what is going on behind the curtain of Christmas morning.

More importantly for our family, we attempt to subvert the narrative — we emphasize where this modern story came from.

Saint Nicholas.

We try to give gifts in a way that embodies what made Nicholas such a positive force in society.

We take Advent seriously and use the season to transform how we live and how we view the world.

And we elevate St. Nicholas as an example to guide our ethics.

We talk about who Saint Nicholas was and what he did. Not as an object to trick kids into good behavior or to get the coolest new item that would bring us pleasure. Not to muffle the holiday spirit, but I think we can do better.

Because, maybe, if we took St. Nicholas seriously, it would turn the world upside down.

Maybe, if we truly honored this saint, it would shape us to also embody everything this season is about.

Maybe St. Nicholas is a reason for the season.

Maybe we need to put St. Nicholas back in Christmas.

I hope the real story of St. Nicholas can make a come back in our culture and be for us an example of how to live rightly in the world.

Because we have a lot to learn from the saint of Myra.

References:

White Trash (by Nancy Isenberg)

https://www.history.com/topics/christmas/santa-claus

http://www.ppgplace.com/events/spirit-of-giving/

The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus (by Adam English)

![Three Reasons We're Lonely - [And Three Responses For Being Less So]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5963d280893fc02db1b9a659/1651234022075-7WEKZ2LGDVCR7IM74KE2/Loneliness+3+update+%283%29.png)